How can I support my child with reading if I’m not a confident reader myself?

If you'd rather watch this as a video instead of reading it, click here:

A lot of children struggle with reading, especially when they are required to read out loud.

I can remember as a child sitting in the classroom at school as the teacher worked their way around the class getting each child to read out the next part of the book. Instead of listening to what was being read, I would be sat, lost in my own world. My logic was if I knew what I was going to read I could perhaps practice it now before they reached me and I wouldn’t sound such a fool when I opened my mouth. I loved reading and often (as a younger child) spent hours reading to my dolls and teddies, (please don’t judge!) but when it came to reading out loud with anyone listening it would all just go to pot.

So, there I would be carefully analysing what my part was going to be and reading it over and over in my head. With any luck the bell would go before the teacher ever got to me and I would be off the hook. An internal monologue would run inside my head: “Good luck. They’re getting closer. Good luck. You’ve practiced this, you’ll be fine. Good luck…”

“Dawn, if you could read the next page, please.”

Fear would grab me and any skill I have ever owned at reading would run for the closest window or door and I would be left floundering with bright red cheeks and a growing threat of crying.

I loved reading and often (as a younger child) spent hours reading to my dolls and teddies, (please don’t judge!) but when it came to reading out loud with anyone listening it would all just go to pot.

When parents get in touch about supporting their children, reading is often an issue that raises its head. In this article we will look at how children learn, some possible reasons some children struggle, and some of the games that I often use to support children with reading (including the dotty board game, which is one of my favourite games and has always proven to be a big hit).

How do we learn?

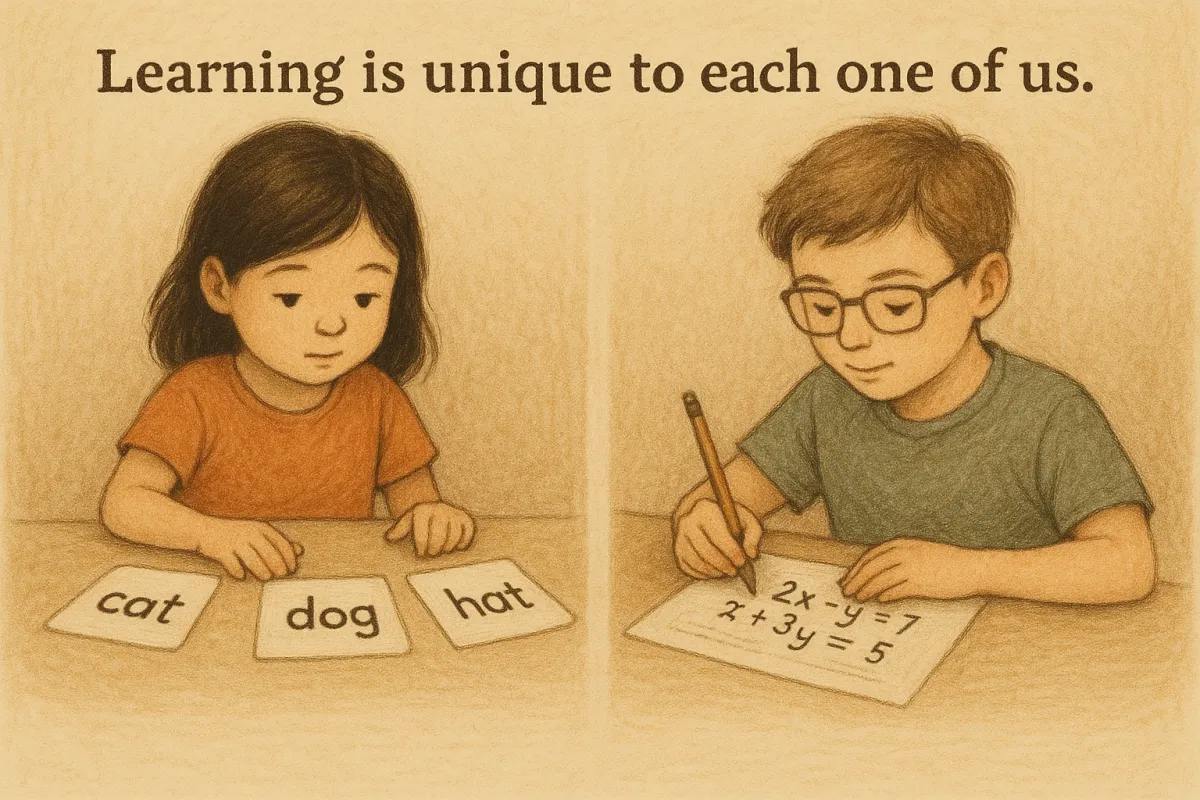

Learning is unique to each one of us. However, there are some principles we can use to support any child’s education that will prove beneficial.

If we give our children something to do to help them learn, we help them create a memory. For a younger child, this might be flashcards to help them recognise basic words, which can then be built upon to help them learn to read.

For an older student, we may give them a worksheet to help them learn non-linear simultaneous equations.

In doing so, we help them create a memory in their brain where they can go to recall that piece of information.

(I’ve used those two examples to show how this is relevant to all levels of students.)

We then play with the flashcards again or give them another worksheet. In doing so, we help reinforce that memory — to make it stronger.

Learning is unique to each one of us. However, there are some principles we can use to support any child’s education that will prove beneficial.

However, When we are in a situation when we aren’t thinking logically, or our natural way of thinking isn’t the linear route that is expected to be the norm, or we are sat in an exam or the teacher just takes it upon themselves to single you out to be the person to answer their question, it is unlikely that our brain will hurry straight to the specific piece of information that we need.

Instead, it starts darting around inside our head like a ping-pong ball looking for that relevant nugget that will save the day. It travels all around the houses, the most scenic route it can possibly find and then often fails to locate that titbit that would have been so appreciated in that moment of time.

Yet, if we give them a second activity to help them learn, it will support them in creating a second place in the brain where they can find this information. Instead of using the flashcards, we might write those same words onto Jenga bricks so that, as you take one from the tower, you must read it before replacing the brick onto the top for the other person to have a go. Or create a pairs game where you match the words to a picture, or a word to a word. You might play bingo, draw images of the words and write the word next to it, make the words out of magnetic or Scrabble letters, or write them in the sandpit or with water on the side of the building.

For the student learning non-linear simultaneous equations, you might ask them to create a poster using large bright colours explaining to their peers how to solve these problems. Or you might create a board game where you need to answer the questions as you go. Code breakers offer another alternative.

The goal is to make the activities as interactive as possible. Use colours — ideally a minimum of five — as this helps open different neural pathways.

This approach also aims to make learning enjoyable. If the child is relaxed, they are more likely to take on the information rather than focusing on the desire not to be doing it.

Furthermore, if they are enjoying themselves, they will be more likely to want to participate — and with participation comes practice. With practice comes ability, and with ability comes confidence. It becomes a positive spiral of success.

Give all the support that they need to help them to succeed

I often use the analogy of when a baby first starts to learn to walk. We hold both their hands, and we are there with them every step of the way. We praise every step and celebrate it out loud, with pure and genuine pride.

Then slowly they gain confidence, and they let go of one of our hands. We are in awe of what they are doing, but we remain closely by their side holding that other hand just in case they need us.

Then one day they let go altogether and they no longer need us. They have the confidence and the ability to walk, to run without us. From that moment, they never look back.

Academic learning is no different. We need to provide that safety net whilst it is needed.

I often use the analogy of when a baby first starts to learn to walk. We hold both their hands, and we are there with them every step of the way. We praise every step and celebrate it out loud, with pure and genuine pride.

What triggered my interest:

When my oldest daughter approached 7 or 8 years old, I thought she might be mildly dyslexic. I had been on a course at the local college, focusing on supporting reading and spelling difficulties. As part of the course, we had to do a case study on someone, so I chose Clara. At the end of the course, the tutor pulled me a side and suggested I had a word with her teacher. So, I plucked up the courage and went in. The response I got was that dyslexia was just an excuse for laziness so there probably wasn’t anything to worry about…

I didn’t have the confidence back then to fight my corner so I thought if I could learn everything I could about different learning styles what I learned would hopefully compliment the degree I was doing at the time, but I could also use it to support her (not that she ever really wanted my help). That was over 20-years-ago now, and I still find it fascinating now.

Why do some children struggle to read?

There’s a whole mix of reasons why some children find reading difficult and it’s not because they’re lazy or not trying hard enough. That’s a myth we need to leave behind. Just like walking, talking, or riding a bike, reading is a skill that takes time, and every child will find their own way in their own time.

Some children might not have had a lot of books or stories around them in those early years, so they’ve had fewer chances to soak up language and build a love of words. Others might struggle to hear sounds clearly or mix up letters and sounds when they try to blend them together. Some might even have vision problems that make the words on the page blur or dance around. And then there’s confidence, if a child has had a tricky start with reading, or they’ve been laughed at or corrected too harshly, they might just shut down and not want to try at all.

But often, the challenges go deeper than that, especially for children who are neurodiverse. Their brains process the world differently, which can make the usual way reading is taught feel frustrating or confusing.

For example:

There’s a whole mix of reasons why some children find reading difficult and it’s not because they’re lazy or not trying hard enough

Dyslexia

can make it harder to link letters with sounds, break down words, or remember spellings — even when a child is bright and creative in so many other ways.

ADHD

might mean a child finds it hard to sit still or stay focused long enough to follow a story, especially if it’s not grabbing their attention. They might skip lines or lose their place mid-sentence.

Autistic children

might be great at reading out loud, but struggle with understanding what the story really means — especially if it involves emotions, idioms, or social situations that don’t feel clear or logical.

Dyspraxia

can affect things like eye tracking and coordination, which you might not think are linked to reading — but actually, they’re really important when it comes to moving smoothly across a page or remembering the order of words.

Auditory processing difficulties

mean some children can’t easily tell the difference between similar sounds, like ‘b’ and ‘d’ or ‘cat’ and ‘cap’. This can make phonics a real minefield.

And for children with working memory challenges, holding onto a full sentence while trying to decode tricky words can be exhausting — like trying to juggle too many things at once.

None of these differences mean a child can’t learn to read. It just means they need different tools, more time, and a whole lot of patience and encouragement.

The most important thing to remember is this: struggling to read is not a reflection of a child’s intelligence or potential. It’s just a sign that we might need to approach things differently — and that’s okay. There’s no one right way to learn, and with the right support, every child can build the skills they need to enjoy reading in their own way.

What can we do as parents to help our children with reading?

Creating a Positive Learning Environment

First and foremost, it’s essential to foster a positive and supportive learning environment at home. Many children often feel self-conscious about their reading abilities, and this can lead to anxiety or a reluctance to engage with books. As a parent, you can help ease this pressure by emphasizing progress over perfection and celebrating every step forward, no matter how small it may seem.

Avoid comparisons with other children or siblings. Each child learns at their own pace, and that doesn't define your child's potential. Encourage their efforts and remind them that it’s okay to struggle sometimes—what matters most is persistence and the willingness to keep trying.

Encourage their efforts and remind them that it’s okay to struggle sometimes—what matters most is persistence and the willingness to keep trying.

Practical Strategies for Supporting Reading at Home

Use Multisensory Learning Techniques

One of the most effective ways to support children in reading is by using multisensory learning methods. Some children often struggle with traditional reading instruction that relies heavily on visual or auditory input alone. Multisensory techniques engage multiple senses such as sight, sound, touch, and movement—making it easier for your child to process and retain information.

For example, you can use letter tiles or magnetic letters to help your child build words physically, which allows them to see and feel the letters as they construct words. You could also encourage them to trace letters in sand or with their finger, pairing the activity with sounds or spoken words. Activities such as these can make learning more enjoyable and less abstract for your child.

Use Assistive Technology

There are many assistive tools and technologies that can support your child’s reading development. Audiobooks are particularly helpful as they allow children to follow along with a narrator while seeing the text. This combination can improve word recognition and comprehension. Many apps and tools are available to help with reading, including text-to-speech programs and apps that highlight words as they are read aloud.

Using coloured overlays or dyslexia-friendly fonts can make reading less visually overwhelming.

Focus on Phonics and Word Patterns

Phonics-based instruction often helps children by teaching them the relationships between letters and sounds. Breaking words down into smaller parts—like syllables, phonemes, and morphemes—can help your child decode words more effectively.

Practice word patterns and rhymes with your child, focusing on the sounds within words. Repetition is key, but it’s important to present practice in a way that doesn’t feel repetitive or tedious. You might play games that involve matching sounds to letters or make up songs or chants to help your child remember common phonics rules.

Read Together Often

Reading with your child is one of the best ways to build their confidence and fluency. Choose books that interest them, even if they are slightly below their reading level. When a child is engaged in a story, they’re more likely to persevere through the challenges. Make reading a regular part of your routine but keep it relaxed and enjoyable—this is not about testing or evaluating their skills.

Being a less confident reader yourself may also be beneficial as it shows your child that it’s actually ok not to be great at it: the person they love/admire most in the world doesn’t find it easy either. You can learn, practice, grow together. You’re in it together for support, guidance and help.

You can take turns reading, with you reading aloud the more difficult sections and letting your child read the parts they feel comfortable with. This takes the pressure off and ensures they can still experience the joy of storytelling. Even now in my 50’s if I’m working with someone and I have to read out loud, I still apologise and tell them that I will probably fall all over my words and sound completely incompetent, so please bear with me and I will do my best.

Reading with your child is one of the best ways to build their confidence and fluency.

Use Positive Reinforcement

Always remember that positive reinforcement is a powerful motivator. Praise your child’s efforts, not just the results. If your child manages to read a particularly tricky word or remembers a rule they’ve struggled with, celebrate it. This can help build their self-esteem and encourages them to keep pushing forward, even when reading feels hard.

Be mindful of the language you use when offering support. Instead of pointing out mistakes, gently guide your child toward the correct answer. For example, if they misread a word, you might say, "Ah, that was so close! Let’s try that word again together."

Partnering with Your Child’s School

Your child’s school plays a crucial role in their reading development, and building a strong partnership with teachers and support staff can significantly benefit your child. Stay in regular communication with their teacher to ensure that you are aware of your child’s progress and the support they are receiving in class.

Building Resilience and Encouraging a Growth Mindset

One of the most valuable lessons you can teach your child is resilience . Reading may be challenging, but it doesn’t define their future success. Encourage a growth mindset by helping your child see that effort leads to improvement, and that struggling with reading doesn't mean they are failing—it’s just part of the learning process.

Remind your child that everyone has strengths and challenges, and that struggling with reading doesn’t make them any less capable than anyone else.

Above all, remember that your child’s journey with reading is unique. Celebrate their progress, no matter how small, and always approach challenges with kindness and understanding. With your support and encouragement, your child can build the skills and confidence they need to overcome the obstacles posed by reading and discover the joy of reading.

Games we use to support reading

Here are 3 of my favourite games.

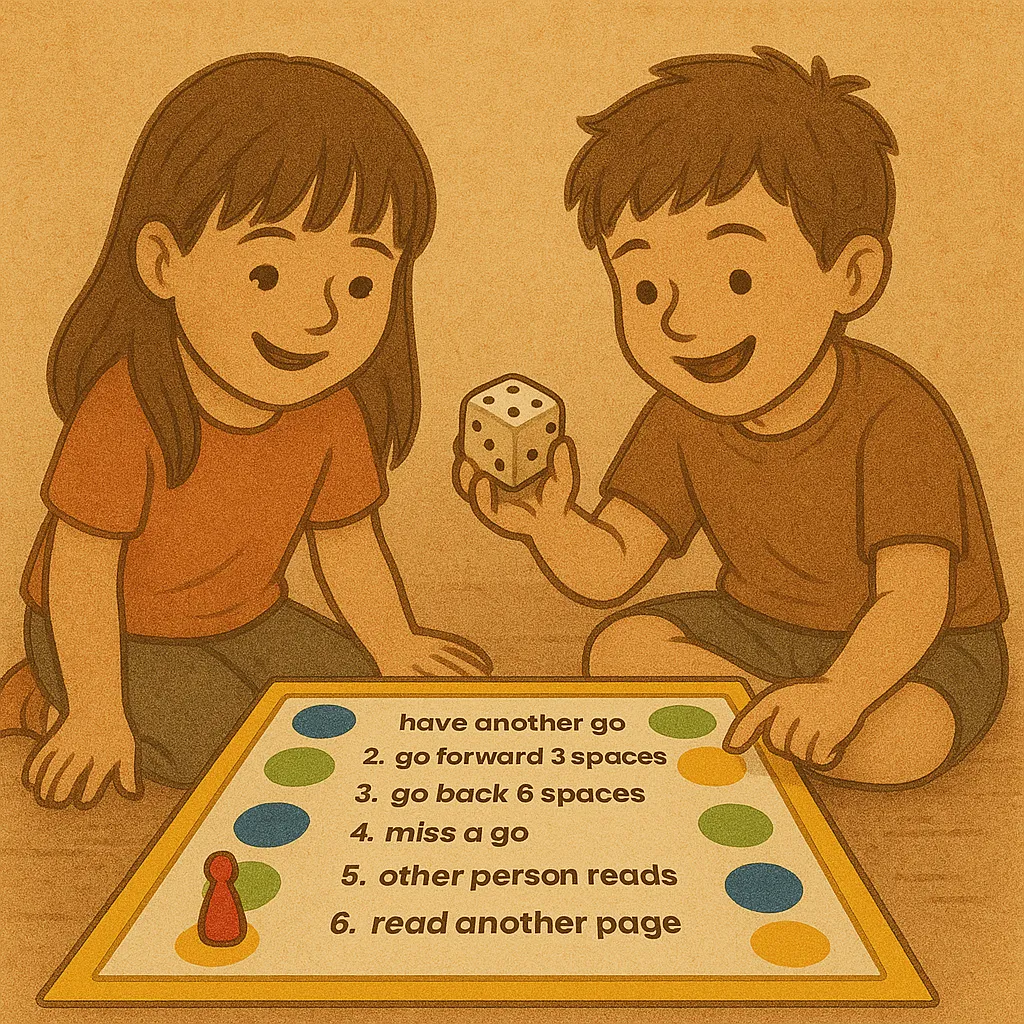

The dotty board game

I’ll start with the dotty board game, as this is one I have used a lot over the past 12+ years. (If you would like a copy of the board, please do drop me a line and I will happily send you a copy over to use yourself: info@clarajamestutoring.co.uk)

Around the board you have 18 dots or images: 6 red, 6 blue, 6 yellow (as an example). We each choose a colour. You can be red, I’ll be yellow.

You can move any direction around the board, but you can not change direction halfway through your go.

Player 1 rolls the dice. The number on it determines how far you can move.

If anyone lands on a red, you will need to read a sentence, paragraph, page, etc depending on what we have agreed is appropriate.

If anyone lands on a yellow, I you will need to read a sentence, paragraph, page, etc depending on what we have agreed is appropriate.

Landing on a blue will lead to a forfeit. You will roll the dice again and this will determine whether:

1) Have another go

2) Move forward 6 spaces

3) Move back 3 spaces

4) Miss a go (you don’t get to roll, but you can still read!)

5) The other person reads

6) You need to read again.

My idea when I came up with this was to take the onus off one person having to put in all the effort as I mentioned earlier, I used to hate reading out. In my head, no problem. As soon as I started reading out loud, I became a bumbling buffoon.

I also felt that if you never knew when your turn was coming it would mean in you had less of an opportunity to sit there in dread because you would also become too caught up in the game.

Silly Sentences

A game I often play with young children is “silly sentences”. Start with a dozen sentences:

The young black dog played.

The lazy brown cat slept.

The wise white owl read.

The fast orange fish swam.

Etc.

You can make them as long or as short as you like, but they all need to have the same structure.

Now cut each of your sentences up and put the corresponding words onto a pile (put the on one pile, the first adjective – describing word, onto another pile, etc).

Now take one word from each pile to form a sentence.

Very often the sentences will make no sense, but that makes them more humorous to read. You can write them down to practice handwriting/ to remind yourself of how funny they were!

It’s fun and not to be taken too seriously.

A game I often play with young children is “silly sentences”. Start with a dozen sentences:

Story boards

Something I often ask children to do that enjoy drawing is, at the end of each chapter draw a story board of the events that have taken place or ask them to draw (and annotate) a character that we are introduced to. This way we can determine that they have understood it, but in a more informal way.

We sometimes deviate from this and create word searches for example using key words, ideas or characters from the section.

Something I often ask children to do is to draw (and annotate) a character that we are introduced to.

Where can I find more help?

I could talk about this all day and give you more ideas of games you could play.

If you’d like more fun, practical ways to help your child with reading I send a weekly email out on a Monday to the parents of primary school aged children and Thursdays to the parents of secondary school aged children with hints on supporting various aspects of maths, English or revision.

But if you’re looking for something a bit more constructive, you might find the Clara James Approach helpful. It’s our membership group where you will find a range of resources you can use to support your child at home. Each month a new bundle is uploaded. In addition you will also have access to the Facebook group where you can gain ideas and advice from myself and others in the group and there is also a monthly zoom call where you can ask questions to me directly.

If you’re interested and want more information, click the link below

Copywrite: Clara James Tutoring 2025